Intro

Gresham’s Law is named after Sir Thomas Gresham, an English financier and merchant who lived during the 16th century and founded the Royal Exchange in the City of London. The law is based on the economic principle that “bad money drives out good,” meaning that less valuable money tends to remain in circulation while more valuable money is hoarded and eventually disappears from daily use. This principle is primarily applied to monetary economics, but it can also be extended to situations where lower-quality goods or services dominate over higher-quality alternatives due to factors like price controls or market distortions.

Classical Definition of Gresham’s Law

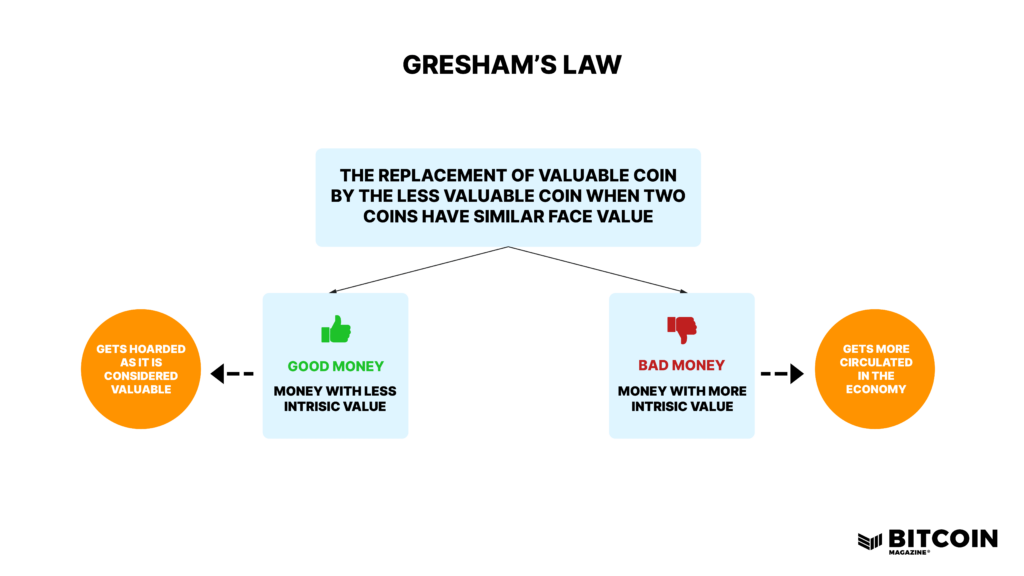

The classical version of Gresham’s Law, expressed as “bad money drives out good,” applies when two types of money are legally circulating, but one has higher intrinsic value than the other. The “bad” money is overvalued by law (often through government-enforced fixed exchange rates or legal tender laws), and the “good” money is undervalued.

For example, in a system where both gold coins and base metal coins are in circulation at the same nominal value, individuals will tend to hoard the gold coins (the “good” money) because they have more intrinsic value. At the same time, they will spend the base metal coins (the “bad” money), which are less valuable. This phenomenon occurs because people want to keep their valuable assets while spending those that are worth less, leading to the disappearance of the more valuable money from circulation.

Thus, the classical definition explains how government policies, like fixed exchange rates between currencies or coins, distort the market and cause less valuable money to dominate everyday transactions.

Rothbard’s Interpretation of Gresham’s Law

Murray Rothbard, a prominent economist in the Austrian school of economics, reinterpreted Gresham’s Law by emphasizing that the phenomenon only occurs when the government imposes price controls. Rothbard argued that the classical definition of Gresham’s Law applies under artificial circumstances, specifically when the government fixes an exchange rate between two forms of money—such as paper currency and coins or different metals in a bimetallic system.

According to Rothbard, under such government price controls, the market value of the “good” money (with higher intrinsic value) is artificially reduced, while the “bad” money (with lower intrinsic value) is overvalued. This misalignment leads people to hoard the undervalued, “good” money and spend the overvalued, “bad” money. However, Rothbard noted that in a free market without such government intervention, the opposite would happen: people would prefer to use good money, and it would eventually drive out bad money.

Rothbard’s definition highlights the importance of government price controls as a key driver behind Gresham’s Law. Without these controls, he believed that the free market would ensure that good money prevails over bad money.

Origin of the Term

Although Gresham’s Law is named after Sir Thomas Gresham, it was not formally defined by him. Gresham, who served as a financial agent to Queen Elizabeth I, observed the principle in action and advised the queen about the consequences of currency debasement. The actual term “Gresham’s Law” was coined in the 19th century by economist Henry Dunning Macleod, who named it in honor of Sir Thomas.

The underlying concept of Gresham’s Law was known long before Gresham’s time. The principle can be traced back to ancient Greece and the work of Aristophanes, who described similar behavior in the economy of Athens.

The Concept Of Gresham’s Law

When two forms of money are both in circulation as legal tender, and one is of higher value and the other is of lower value, people tend to stack and save the money with higher intrinsic value and spend or circulate the money with lower intrinsic value.

To be designed

The law makes sense when applied to coins’ overall tangible value based on the metals’ composition used to make them. Gresham’s law applications have been rare since the modern transition to fiat currencies and paper money. However, we will see later in the article how bitcoin is a suitable example of the good money adopted alongside the bad money in the digital age.

Continuous currency debasement in today’s markets has caused a constant trend of inflation in most economies worldwide, with instances of hyperinflation where money isn’t even worth the paper it’s printed upon. Debasement occurs to reduce something’s value; for coinage, it means to reduce the amount of precious metal in coins but keep the face value constant.

The Principle Of “Bad Money Drives Out Good”

Gresham’s law states that “the bad currency drives out the good,” which relates to a time when the economy made all transactions with coins. It has origins in currency debasement, which established that precious metal coins and coins made with a mix of different base metals had the same value.

Suppose there are two types of coins in circulation: one made of gold and another made of base metal. Both coins are considered legal tender, but the gold coin has a higher intrinsic value due to its metal content. In this scenario, people would prefer to hold onto the more valuable gold coins and use the base metal coins for everyday transactions.

As a result, the good money (gold coins) tends to be hoarded or taken out of circulation, while the bad money (base metal coins) remains in circulation. This phenomenon occurs because individuals prefer to hold onto money that retains its value and spend the money that is becoming worth less.

Why Is It Important?

While the world has moved away from coinage, Gresham’s law still holds significance in the modern economy, whenever two forms of money are circulated and in the presence of legal tender laws when the law mandates currency units to be recognized at an identical face value.

Without effectively enforced legal tender law, good money will drive out bad money because individuals can simply reject the less valuable currency as a payment method for transactions.

Gresham’s law helps explain the patterns of circulation and acceptance of different currencies within an economy. Understanding the law helps policymakers and economists recognize the potential consequences of debasement and the erosion of trust in the currency, which is essential to maintain a stable monetary system.

The Reverse Of Gresham’s Law

The reverse of Gresham’s law can also occur, although both situations are not necessarily in contrast. Thiers’ law, for instance, remarks that good money will drive out bad money, the opposite of what Gresham’s law states. Thiers’ law occurs when a currency decreases in value so much that even merchants won’t accept it.

Even if the currency is legal tender in the country where this happens, and it should be illegal to reject it as a means of payment, such imposition is generally ignored by the citizens who will abandon it in favor of more valuable currencies. Especially in times of hyperinflation, more stable foreign currencies typically replace local currencies, an example of the Thiers’ law.

Historical Examples Of Gresham’s Law

Coinage In Ancient Rome

One of the most significant historical examples of Gresham’s law is related to the currency debasement in Ancient Rome due to the decline of the Roman Empire. In the third century AD, to face the growing expenses of military campaigns, the Roman government had to cut down on the quality of its coins and reduce the amount of silver in them while maintaining their face value.

According to Gresham’s law, people preferred to hoard the older, higher-quality coins or use them in transactions where the value of silver mattered, such as international trade. At the same time, the debased coins were legal tender and remained in circulation for day-to-day transactions within the empire.

The Great Recoinage Of 1696 In England

Another excellent example of Gresham’s law in history was the Great Recoinage of 1696 in England when the country’s currency faced a problem of debasement and widespread counterfeit coins. It was an attempt by the English government under King William III to restore the currency’s integrity, remove the debased and counterfeit coins from circulation and replace them with new silver coins.

The old coins’ intrinsic value (weight) had been reduced so much that they were no longer a viable tender, especially abroad, and had to be exchanged with the new silver coins. However, the recoinage resulted in about 10% of the nation’s currency being formed of forged coins. Furthermore, the Royal Mint was unprepared to replace the monetary base and had only minted about 15% of the silver coins needed for the exchange.

With an increasing value of the silver, constant outflow of the precious metal in the continent led to arbitrage opportunities, with the new good “milled” coinage being hoarded and exported to this “arbitrage” market, while the badly “clipped” coinage remained in circulation. This is a perfect example of Gresham’s law in action.

The American Revolution

American colonies faced significant economic challenges, including issues with their currency, during the American Revolution. As tension escalated between them and the British government, the supply of British currency became limited, and the colonial governments started issuing their own paper money.

The uncontrolled printing of money without adequate backing led to a rapid depreciation of the local currency, further worsened by the people’s increasing lack of faith in the currency, so its purchasing power declined significantly.

This depreciation and lack of trust created an environment where the “bad money” (continental currency) drove out the “good money” (British coins), precisely as Gresham’s law expects. The British coins were considered “good money” because they retained their intrinsic value, while the American currency became increasingly worthless.

Gresham’s Law In Modern Economy

Fiat Money And Commodity Money

Gresham’s law continues to have relevance in modern economies, particularly when examining the interaction between fiat money, backed by people’s trust, and commodity money that derives its value from the underlying commodity it represents, like gold or silver.

In the context of Gresham’s law, when fiat money and commodity money coexist, there is a potential for the “bad money” (fiat money) to drive out the “good money” (commodity money) as people tend to hoard and store commodity money but use fiat money for everyday transactions.

Fiat money relies on its widespread acceptance and legal tender status, and it has become the more convenient and commonly used medium of exchange. People may be reluctant to part with their commodity money in transactions, resulting in its limited circulation compared to fiat money.

Hyperinflation And Gresham’s Law

In the context of Gresham’s law, hyperinflation can profoundly impact the dynamics of currency circulation and the interaction between different forms of money. During hyperinflation, people lose confidence in the domestic currency, triggering behaviors in line with Gresham’s law.

They start hoarding stable and more reliable currencies, precious metals, or commodities like bitcoin, considered “good money” compared to the rapidly depreciating domestic currency. During hyperinflation, the rapid loss of confidence in the domestic currency and the search for more stable alternatives can intensify the tendency for bad money to drive out good money, which may lead to further erosion of the domestic currency’s value and contribute to the breakdown of the monetary system.

Gresham’s Law In The Digital Age

There is a great example of Gresham’s law in the current digital age: the coexistence of bitcoin with fiat currencies. In the presence of two currencies — bitcoin and one fiat currency like the dollar — individuals and organizations tend to hold on to the bitcoin, which has grown more valuable over time than the bad money (the U.S. dollar in this instance, which tends to retain its same value, or even trend towards having lower value.)

While bitcoin’s impact on the traditional monetary systems is in its infancy, its coexistence with fiat currencies relates to Gresham’s law, where multiple forms of money are legal tender and used simultaneously. Bitcoin is the first example in the modern era of bad money that drives the good money out of circulation, because people tend to stack, or save, the more valuable money.

However, bitcoin’s use as a medium of exchange faces challenges due to factors such as price volatility and limited acceptance, and its circulation as a day-to-day currency remains relatively limited. Furthermore, the perception that bitcoin may appreciate over time can lead to a reluctance to spend it, which can hinder its circulation and adoption as a medium of exchange.

This should not necessarily be viewed as a negative. According to Gresham’s law, “Good and bad coin cannot circulate together,” so it’s rational to spend fiat and HODL bitcoin, thus delaying its use as a medium of exchange. This is where Nakamoto and Gresham meet. When fiat is no longer viable as a medium of exchange, or when individuals receive the entirety of their earnings in bitcoin and can pay everything with it, only then will it make sense to use bitcoin as a medium of exchange on daily transactions.

Read More: >> How Does Gresham’s Law Relate To Bitcoin

Conclusion

Gresham’s law provides insights into the interaction between different forms of money in modern economies, highlighting the potential for inferior forms of money to displace superior ones based on factors such as convenience, trust, and intrinsic value.

In modern economies, fiat money is the predominant form of currency, and commodity money has largely been phased out. However, Gresham’s law remains relevant where alternative forms of digital currency like bitcoin have emerged with intrinsic value in the form of cryptographic technology and limited supply.